When it comes to behavior support in schools, getting clear on the problem behavior is the first critical step. But too often, teams use vague language like “he’s being disrespectful” or “she’s just noncompliant.” These labels can spark debate, feel emotionally charged, and worst of all—they don’t help us support the student effectively.

That’s where writing an operational definition of the target behavior comes in.

Why Does a Clear Operational Definition Matter?

Writing a behavior as a specific, observable, and measurable action helps in several powerful ways:

- It gets everyone on the same page. Teachers, paras, and specialists all know exactly what to look for.

- It removes emotion. Labels like “defiant” or “lazy” aren’t helpful. Objective language keeps the focus on support, not blame.

- It gives us something to measure. We can track frequency, duration, or intensity—and know if things are improving.

- It clarifies what to teach. When we know what the behavior looks like, we can plan clear replacement skills.

Clinical Use: Defining a Target Behavior

In clinical and educational settings, a target behavior should be written with two parts:

- Target Behavior Label: Select or create a label that concisely identifies the behavior being assessed.

- Operational Definition: Define the behavior in specific, observable, and measurable terms.

Hint: Describe the target behavior as if a video camera were recording the student. What would it see and hear?

For example:

- Less Effective: Disruption = will not pay attention and wants to control the classroom.

- Better: Disruption = making inappropriate and/or off-topic comments during instructional times.

If you are struggling to write your BIP, check our dedicated guide!

5 Examples of Target Behaviors (and What Not to Do)

Let’s look at five common behaviors—paired with vague non-examples—so you can write better behavior descriptions that actually guide support.

1. Aggression

Non-Example: “Student becomes aggressive when upset.”

Better Definition: “Student hits others with a closed or open hand, kicks furniture or people, or throws classroom objects more than 2 feet.”

Why it works: It describes exactly what aggression looks like, in a way anyone could observe and record.

2. Work Refusal

Non-Example: “Student refuses to do work.”

Better Definition: “Student remains seated with arms crossed, places head on desk, or verbally says ‘I’m not doing this’ after being prompted to begin independent work.”

Why it works: Multiple observable actions that represent refusal, with a clear context (after prompt).

3. Noncompliance

Non-Example: “Student is noncompliant during group.”

Better Definition: “Student does not follow teacher instructions (e.g., ‘Please join the group on the rug’) within 10 seconds of the direction being given.”

Why it works: Adds a time frame and an example, making it clear when noncompliance starts.

4. Disrespect or Defiance

Non-Example: “Student acts disrespectful.”

Better Definition: “Student rolls eyes, mimics staff in a sarcastic tone, or says phrases such as ‘Whatever,’ or ‘You’re not the boss of me’ after receiving a correction.”

Why it works: Captures how disrespect is expressed in observable, repeatable ways.

5. Tantrum

Non-Example: “Student has a tantrum when they don’t get their way.”

Better Definition: “Student cries loudly, throws self to floor, kicks legs, and screams for longer than 30 seconds following a denied request.”

Why it works: Describes what the tantrum includes, how long it lasts, and what triggers it.

Selecting Which Target Behavior(s) to Assess

Students often display multiple behaviors that interfere with learning, socialization, and/or safety. To focus your functional behavior assessment (FBA) and behavior plan, consider these two options:

1. Group Behaviors into a Response Class

Some behaviors serve the same purpose or occur in similar situations. In those cases, it may be appropriate to group them into a Response Class and assess them as a single unit.

Example: Blurting out, disruption, and minor property destruction all occur during writing activities and appear to serve the function of getting the teacher’s attention. These could be combined into a single Response Class for assessment and planning.

Only use this approach if the behaviors clearly share a similar function or environmental triggers.

2. Prioritize High-Impact Behaviors

If there are too many behaviors to assess at once, prioritize the most disruptive or dangerous first. A well-designed plan that reduces one high-priority behavior can often decrease related behaviors as well.

Example: If a student exhibits aggression, work refusal, and inappropriate gestures, prioritize aggression. Once that improves, you can revisit and target additional behaviors.

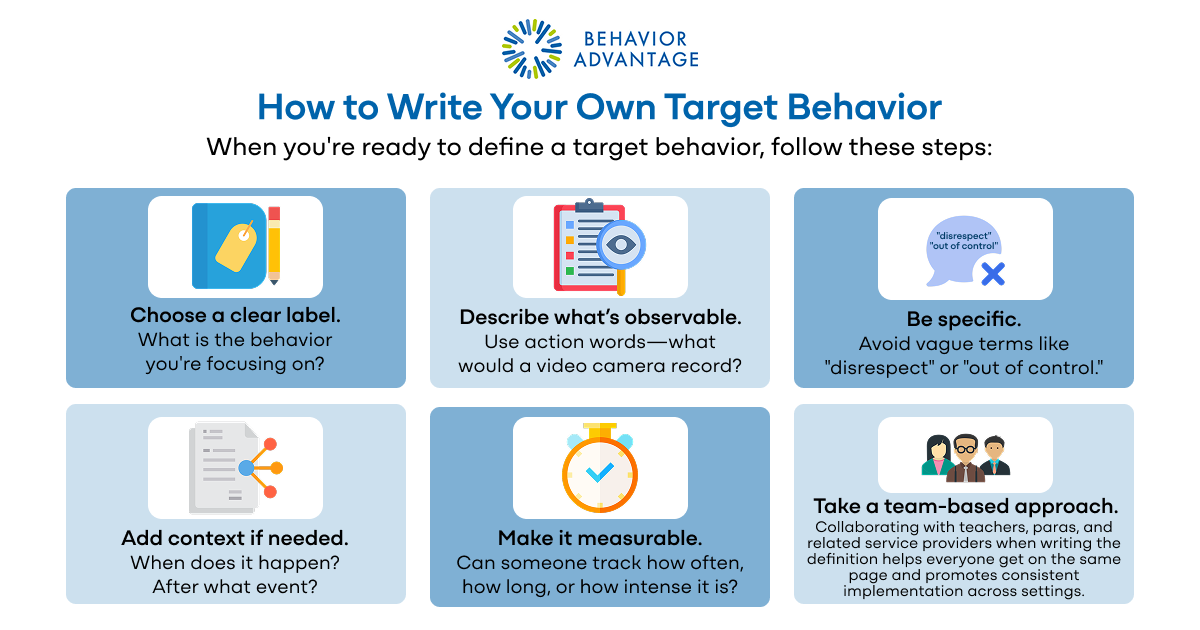

How to Write Your Own Target Behavior

When you’re ready to define a target behavior, follow these steps:

- Choose a clear label. What is the behavior you’re focusing on?

- Describe what’s observable. Use action words—what would a video camera record?

- Be specific. Avoid vague terms like “disrespect” or “out of control.”

- Add context if needed. When does it happen? After what event?

- Make it measurable. Can someone track how often, how long, or how intense it is?

- Take a team-based approach. Collaborating with teachers, paras, and related service providers when writing the definition helps everyone get on the same page and promotes consistent implementation across settings.

Want more support writing behavior goals based on these definitions? Check out our blogs: How to Write Smart Behavior IEP Goals and IEP Goal Bank.

Final Thoughts

Writing clear target behavior examples takes a little practice—but once you start using specific, observable, and measurable language, everything else becomes easier: collecting data, choosing strategies, tracking progress, and training others.

Bonus Thought: Clear operational definitions don’t just work for problem behaviors—they’re also a powerful way to define the replacement behaviors you want to teach. If we apply the same principles to teaching new, positive behaviors, our behavior plans become more effective. Instead of just hoping students figure out how to be “respectful” or “responsible,” we define exactly what that looks like and give them the tools to succeed.

Stay tuned for our next blog post, where we’ll take the same five examples from this article and show you 20 replacement behaviors—each tailored to the function of the original problem behavior.

Once you start using specific, observable, and measurable language, everything else becomes easier: collecting data, choosing strategies, tracking progress, and training others.

At Behavior Advantage, we help school teams write better BIPs and behavior goals using operational definitions that work. If you’re looking to strengthen your behavior planning system, try our platform or explore our Professional Development Series.

Let’s stop guessing—and start defining behaviors that lead to real change.