Behavior intervention plans (BIPs) are meant to support students, guide educators, and create clarity for everyone on the team. But too often, BIPs fall short of their purpose. They end up being long, compliance-driven documents that check the boxes while failing to produce meaningful, sustainable change in the classroom.

At Behavior Advantage, our team of Board Certified Behavior Analysts (BCBAs) works with hundreds of educators, specialists, and administrators each year. Across states, districts, schools, and programs, we continue to see the same challenges: BIPs that are written alone, are unrealistic in practice, or are so packed with strategies that implementation becomes impossible.

A strong BIP, on the other hand, is collaboratively built, function-based, practical, teachable, and progress-monitored. When done well, it empowers educators and helps students build the skills they need to succeed.

Here are five of the biggest mistakes to avoid when writing a behavior intervention plan – and what to do instead.

Not sure what a BIP is? You can read more about it here.

1. Writing the Plan in Isolation

One of the most common mistakes is writing a BIP alone and then handing it off to teachers and staff with the hope they’ll follow it.

But behavior support doesn’t work like that. A plan created in isolation may look good on paper, but it often reflects only one person’s understanding of the problem, the environment, and the student. It also misses vital input: the teacher’s lived experience, the paraeducator’s insights, the student’s voice, and the parent’s perspective.

Why this matters:

A BIP is only as strong as the team that stands behind it. If a plan is written without collaboration, buy-in and fidelity are diminished from the beginning. Teams are asked to implement strategies they didn’t help create, and those strategies may not align with the realities of the classroom or the student’s needs.

What to do instead:

Build the plan together. Invite the teacher, the para, the psychologist, the counselor, the administrator and, when appropriate, the student and family, into the process. This doesn’t mean a three-hour meeting. It means purposeful collaboration:

- Reviewing FBA or functional problem solving togethe

- Checking accuracy and shared understanding of context and function

- Co-designing replacement behaviors and teaching strategies

- Agreeing on what is realistic and doable in the current setting

A collaboratively developed BIP increases ownership, clarity, and commitment which leads to stronger implementation and real student growth.

If you are wondering where to start, check out our comprehensive guide on how to write effective BIPs!

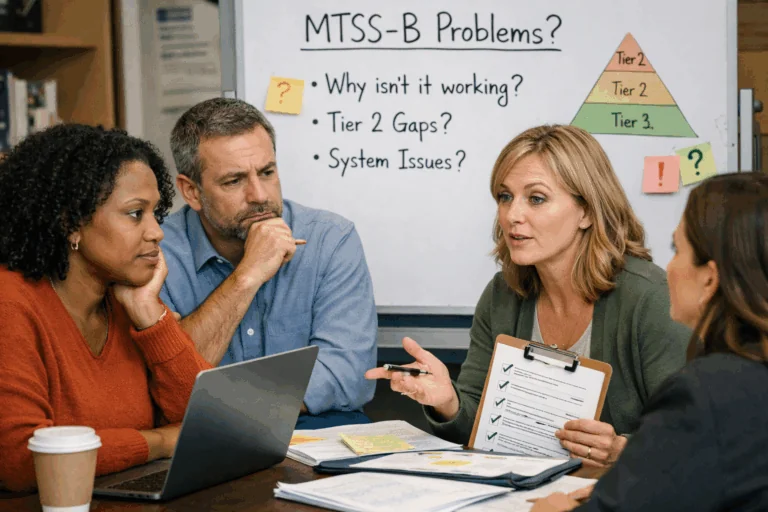

2. Creating a Plan That Isn’t Practical

Even the most beautifully written BIP is meaningless if it cannot be implemented. One of the most frequent issues we see is plans that include too many strategies, too many environmental changes, too many highly individualized instructions or target too many behaviors to realistically carry out in a busy classroom.

Educators want to support students. They’ll try anything. But no plan should require superhuman effort or daily reinvention.

Why this matters:

Overly complex plans lead to burnout, inconsistency, and frustration. They create situations where staff pick and choose what to implement – not because they don’t care, but because it is simply unmanageable.

What to do instead:

Keep the BIP practical. Ask:

- Can this plan actually be implemented in this classroom?

- Does the teacher have the capacity and support needed?

- Can the student realistically access this intervention throughout the day?

- Is this strategy essential, or is it optional noise?

A strong BIP should be concise, clear, and doable. A small number of high-leverage strategies implemented consistently is far more effective than a long list implemented occasionally.

Remember: simplicity isn’t a weakness, it’s a requirement for fidelity.

We have prepared a list of example BIPs for you and your team to explore and take notes on!

3. Failing to Teach and Rehearse Replacement Behaviors

A frequent and problematic mistake is assuming that simply telling a student what to do, or what not to do, is enough to change behavior. Many plans describe the replacement behavior, but they don’t actually outline how the student will be taught, prompted, and reinforced to build that skill over time. Even worse, these expectations are often communicated only during escalation, when a student is least able to process new information or use a new strategy effectively.

New behaviors do not emerge in the moment of crisis. They must be taught proactively, rehearsed when the student is calm, and reinforced consistently so the skill becomes a true habit the student can access when they need it most.

Simply put: if a student has never been taught and practiced the replacement behavior, it is unreasonable to expect them to use it under stress.

What to do instead:

Clearly outline how the replacement behavior will be taught, rehearsed, and prompted, including:

- When instruction will occur

- Who will teach it

- What modeling or visuals will be used

- How guided practice will be built in

- Which prompts will be faded over time

- How staff will reinforce the behavior immediately and consistently

When replacement behaviors are treated like academic targets – explicitly taught, rehearsed, and reinforced – students gain the tools they need to respond more appropriately and independently.

Check out our Behavior Advantage Practical Strategy video on Practicing, Role-Playing, and Rehearsing Skills for tips on how to apply this approach.

4. Using Response Strategies That Only Address the Peak of Escalation

Many response strategies listed in BIPs are well-intended but narrow. They may focus almost entirely on what staff should do when the student is already at the highest level of escalation – during a major disruption, physical aggression, or a full crisis moment. While guidance for those situations is important, a plan that only addresses late-stage behaviors misses the most powerful opportunities for support.

When teams do not recognize and respond to early triggers and warning signs, they lose critical intervention moments where behavior could have been redirected, de-escalated, or even fully prevented. Focusing solely on peak behaviors leaves staff reactive rather than proactive, and it often results in more severe incidents that feel sudden but were actually predictable (and preventable).

Why this matters:

Students almost always show subtle changes – body language, facial tension, increased movement, avoidance, verbal cues – well before reaching a crisis. If the BIP doesn’t guide staff to act during those early stages, interventions come too late to make a meaningful impact.

What to do instead:

Design levelized responses aligned to the student’s individual escalation pattern. For example:

-

- Level 1: Triggers or Antecedents

- Provide a quiet cue or visual reminder

- Adjust demands or offer a brief regulation opportunity

- Level 2: Early Signs of Escalation

- Provide structured choices

- Offer pre-planned break options

- Behavior Redirection that corrects the behavior without a ‘power struggle’

- Level 3: Increased Escalation

- Reduce demands until de-escalation has occurred

- Model a calm and neutral tone – co-regulate with the student

- Reduce communication and directives

- Level 4: Peak Target Behavior/ Crisis

- Follow crisis procedures and prioritize safety

- Minimize verbal engagement

- Level 1: Triggers or Antecedents

-

- Level 5: Recovery & Restoration

- Support regulation and reintegration

- Return to expectations using a neutral tone

- Explore restorative actions to repair and learn

- Level 5: Recovery & Restoration

By addressing early stages, not just the crisis, teams prevent many high-intensity incidents and create a more supportive, predictable environment for students and staff.

Looking for resources on response strategies? You can find practical guidance in our article on Verbal De-escalation Strategies.

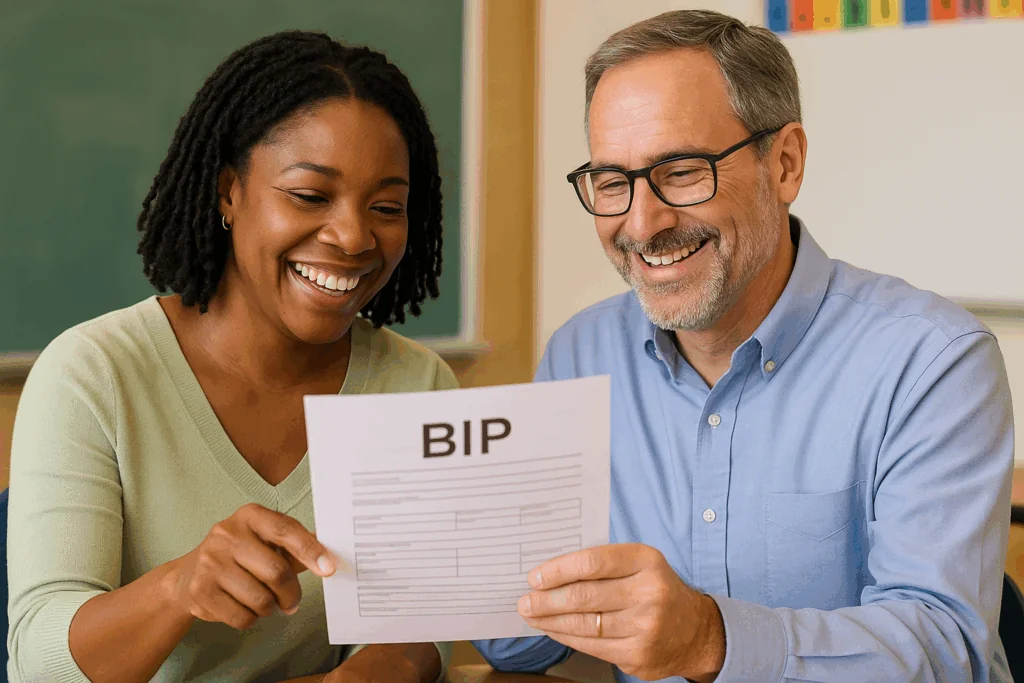

5. Not Collecting Progress Monitoring Data

A plan that is written but not monitored is not a plan, it’s more of a wish.

Accurate and consistent data to track student progress is often hard to come by. Teachers and staff are busy trying to implement the plan while managing the rest of the classroom, so data collection can easily fall by the wayside. Sometimes we also ask teachers to collect too much data, making the task overwhelming and leading to frustration or inaccurate information. Without clear, manageable data to review, teams end up relying on general impressions of how things are going. While those impressions are well-intentioned, they don’t always show whether real skill growth or behavior change is happening, especially since meaningful progress usually takes time and rarely follows a straight line.

Why this matters:

Effective progress monitoring must answer two critical questions:

- Is the student reducing the target behavior?

- Is the student developing and using the replacement behavior?

If either part is missing, teams make decisions based on half the picture. Without solid, consistent data, the BIP cannot evolve and behavior support becomes guesswork rather than guided problem-solving.

What to do instead:

- Track both the target and replacement behavior.

- Use simple, consistent data tools.

- Graph and review the data regularly (e.g., weekly, biweekly, or monthly).

- Adjust the plan based on what the data show, not assumptions.

A BIP should be a living document, continually shaped by real-time data. Behavior Planning Tools can be a very effective way of gathering and organising data – learn more about them here.

Final Thoughts

Strong behavior intervention plans are not long, complicated documents. They are clear, collaborative, realistic, teachable, and built to evolve. When teams avoid these five common mistakes, they create plans that are both effective and sustainable.

When educators understand the why, the how, and the when of the intervention – and when the plan matches the realities of the classroom and the needs of the student – implementation improves, student outcomes improve, and the entire system becomes more supportive and predictable.

Behavior Advantage is built around these principles: practical guidance, evidence-based tools, and a collaborative workflow that helps schools design plans that work, not just in theory, but in practice.

If you’re interested in learning how our platform can strengthen your behavior systems, streamline plan development, and support sustainable implementation, you’re invited to schedule a collaborative demo session to explore our tools and resources.